No doubt you're aware that it's easier and more cost-effective to

sell to existing clients than to new ones. That's reflected in the fact

that 70% of architectural and engineering firms' work comes from repeat

clients. So naturally most firms make it a priority to sell additional

services—what's called cross selling—to existing clients.

Unfortunately, this common-sense approach falls short more often than

not. Lack of success with cross selling is among the most common

complaints I hear when helping firms improve their rainmaking process.

Why is this so difficult? Here are the reasons I uncover most often, and

what you can do to overcome them:

Discomfort selling outside your area of expertise.

Not that this is a legitimate reason why cross selling doesn't work, but

it certainly qualifies as a popular excuse. Ironically, many of these

same professionals who feel inadequate to cross disciplinary boundaries

to talk to clients about their needs will gladly pass the torch to the

firm's business development specialist— despite that individual's lack of technical credentials.

Solution: Specific expertise can be a hindrance rather than a help

in sales. It tempts you to look for problems that fit your skills

rather than openly exploring needs from the client's perspective. Learn

to ask great questions and develop your general problem solving abilities. Then bring in the proper expertise when necessary.

Management inadvertently promotes a lack of cooperation between business units. The

fact is that many firm leaders complain about the paucity of cross

selling while ratcheting up the pressure for individual business units

to meet their sales budgets. You can't expect people to look out for the

greater corporate good when the focus (and the pressure) is

predominantly on how well their own group performs.

Solution: Reward people for succeeding at cross selling, or

dispense with the notion that it will ever work. The firms that excel at

cross selling are typically those that actively promote cross-business unit collaboration in general. Or better still, they organize as a single profit center to minimize the inter-company competition.

The difficulty of engaging different buyers within your clients' organizations.

In concept, it seems straightforward to expand business with your best

clients. But the reality is often quite different. For much the same

reason as my previous point, your current client contacts may not be

that motivated to introduce your firm to other parts of their organization.

They may love you, but what's in it for them? Plus they may not know

their colleagues in other business units well enough to provide you much

leverage.

Solution: Selling succeeds when you can create win-win

scenarios. The same is true in motivating your clients to help you cross

sell. Focus on those opportunities where it's in their interest

for you to serve other parts of their organization. For example, can

you export a winning solution or approach to another business unit where

your client contact gets the credit?

Distrust in your colleagues to deliver. Most

professionals are understandably reluctant to entrust their client

relationships to peers who might not uphold the same standard of care.

So they resist cross selling efforts involving individuals or groups

they aren't confident will come through. This situation is far more

common than many firms recognize because it's rarely discussed openly.

Solution: If you suspect this problem exists in your firm,

it's best to investigate it through private conversations. To encourage

transparency, avoid taking sides or putting people on the

defensive—simply uncover the facts (remember, perceptions in such

matters effectively form the reality of the situation). Once you feel

you understand the concerns, then work with the involved parties to try

to resolve the issues identified.

Lack of client focus. I once participated in a

planning meeting where one of the firm's executives began sketching a

matrix that listed their top clients and what services they were

providing to each. The purpose of this exercise was to identify where

their best cross selling opportunities existed. But the most important

question was ignored: What other needs do our clients have that we might

help them with?

Perhaps the most prominent reason cross selling doesn't work is the

lack of true client focus. When you approach the issue motivated by self

interest, you're unlikely to have many productive conversations with

clients about new services. Don't you think they can detect what's

really driving your interest in the subject?

If you're genuinely motivated to serve your clients, cross selling

becomes a natural byproduct of your commitment to help. It's driven by

the client's needs, not your firm's desire to sell more. Plus, client

focus is the secret to overcoming most of the problems listed above.

There should be no discomfort in serving, no lack of incentive to help

clients succeed. Navigating the client's organization is easier when you

offer true business value. And subpar service and quality within your

firm is no longer tolerated.

So my advice for cracking the code on cross selling is this: Pursue a

culture of true client focus. It's not a quick fix, but it is the most

powerful way to solve your shortcomings at cross selling—not to mention a

whole host of other corporate benefits.

No doubt you're aware that it's easier and more cost-effective to

sell to existing clients than to new ones. That's reflected in the fact

that 70% of architectural and engineering firms' work comes from repeat

clients. So naturally most firms make it a priority to sell additional

services—what's called cross selling—to existing clients.

Unfortunately, this common-sense approach falls short more often than

not. Lack of success with cross selling is among the most common

complaints I hear when helping firms improve their rainmaking process.

Why is this so difficult? Here are the reasons I uncover most often, and

what you can do to overcome them:

Discomfort selling outside your area of expertise.

Not that this is a legitimate reason why cross selling doesn't work, but

it certainly qualifies as a popular excuse. Ironically, many of these

same professionals who feel inadequate to cross disciplinary boundaries

to talk to clients about their needs will gladly pass the torch to the

firm's business development specialist— despite that individual's lack of technical credentials.

Solution: Specific expertise can be a hindrance rather than a help

in sales. It tempts you to look for problems that fit your skills

rather than openly exploring needs from the client's perspective. Learn

to ask great questions and develop your general problem solving abilities. Then bring in the proper expertise when necessary.

Management inadvertently promotes a lack of cooperation between business units. The

fact is that many firm leaders complain about the paucity of cross

selling while ratcheting up the pressure for individual business units

to meet their sales budgets. You can't expect people to look out for the

greater corporate good when the focus (and the pressure) is

predominantly on how well their own group performs.

Solution: Reward people for succeeding at cross selling, or

dispense with the notion that it will ever work. The firms that excel at

cross selling are typically those that actively promote cross-business unit collaboration in general. Or better still, they organize as a single profit center to minimize the inter-company competition.

The difficulty of engaging different buyers within your clients' organizations.

In concept, it seems straightforward to expand business with your best

clients. But the reality is often quite different. For much the same

reason as my previous point, your current client contacts may not be

that motivated to introduce your firm to other parts of their organization.

They may love you, but what's in it for them? Plus they may not know

their colleagues in other business units well enough to provide you much

leverage.

Solution: Selling succeeds when you can create win-win

scenarios. The same is true in motivating your clients to help you cross

sell. Focus on those opportunities where it's in their interest

for you to serve other parts of their organization. For example, can

you export a winning solution or approach to another business unit where

your client contact gets the credit?

Distrust in your colleagues to deliver. Most

professionals are understandably reluctant to entrust their client

relationships to peers who might not uphold the same standard of care.

So they resist cross selling efforts involving individuals or groups

they aren't confident will come through. This situation is far more

common than many firms recognize because it's rarely discussed openly.

Solution: If you suspect this problem exists in your firm,

it's best to investigate it through private conversations. To encourage

transparency, avoid taking sides or putting people on the

defensive—simply uncover the facts (remember, perceptions in such

matters effectively form the reality of the situation). Once you feel

you understand the concerns, then work with the involved parties to try

to resolve the issues identified.

Lack of client focus. I once participated in a

planning meeting where one of the firm's executives began sketching a

matrix that listed their top clients and what services they were

providing to each. The purpose of this exercise was to identify where

their best cross selling opportunities existed. But the most important

question was ignored: What other needs do our clients have that we might

help them with?

Perhaps the most prominent reason cross selling doesn't work is the

lack of true client focus. When you approach the issue motivated by self

interest, you're unlikely to have many productive conversations with

clients about new services. Don't you think they can detect what's

really driving your interest in the subject?

If you're genuinely motivated to serve your clients, cross selling

becomes a natural byproduct of your commitment to help. It's driven by

the client's needs, not your firm's desire to sell more. Plus, client

focus is the secret to overcoming most of the problems listed above.

There should be no discomfort in serving, no lack of incentive to help

clients succeed. Navigating the client's organization is easier when you

offer true business value. And subpar service and quality within your

firm is no longer tolerated.

So my advice for cracking the code on cross selling is this: Pursue a

culture of true client focus. It's not a quick fix, but it is the most

powerful way to solve your shortcomings at cross selling—not to mention a

whole host of other corporate benefits.

If you're not a strong writer, the last thing you want to do is take a stream-of-consciousness

approach to writing. Yet that's what I routinely observe among the

technical professionals I work with. The result is often akin to this

excerpt from an engineering firm's project management handbook:

If you're not a strong writer, the last thing you want to do is take a stream-of-consciousness

approach to writing. Yet that's what I routinely observe among the

technical professionals I work with. The result is often akin to this

excerpt from an engineering firm's project management handbook:

Some documents are constrained to repetitiveness by factors such as regulatory requirements, work type, site information, and intent. In such cases, it is permissible to develop standard language to maximize consistency and efficiency. In such instances, a special review of the standard language must be performed to verify that applicable regulations and requirements have been considered.

Huh?

I'm sure if I asked the author what he meant, he could explain it

clearly to me. But by putting little forethought into his writing he

ended up with something that was incomprehensible. It's one thing to do

this in an internal document, but I commonly see this kind of writing in

proposals, reports, letters, emails, and other communications with

clients and other outside parties. That's hardly a good reputation

builder!

The

poor writing I see is largely the outcome of a thinking problem—or more

precisely, an unthinking problem. In an industry populated by really

smart people, there's no excuse for writing without first thinking about

what you're trying to say. Perhaps it would help to have a process for

planning your writing. Here are some suggested steps:

Think in terms of bullet points. When you jump right into writing without a plan, there's a tendency to get too caught up in how you're saying it before you've really determined what to say. Have you ever spent an inordinate amount of time writing your first few paragraphs? I have—when I didn't plan first. At the start, don't think about sentences—and certainly not paragraphs—think in terms of bullet points. Build your detailed content outline (as described below) by listing short phrases like "slow air flow a concern" or "compressed schedule is key" before you write any sentences.

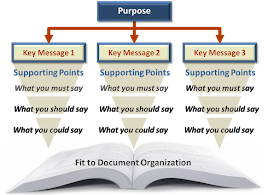

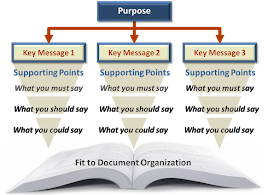

First define your purpose.

Power Writing is writing to achieve a specific desired result. That

obviously means you must first define what it is you want to accomplish.

Sounds simple enough, but identifying the purpose of writing

assignments is surprisingly uncommon in A/E firms. It's important to be

specific. For example: "The purpose of this report is to show that the

extent of contamination at the site is considerably less than previously

determined."

Then determine your key messages. These

are 3-5 points that need to be effectively communicated to accomplish

your purpose. One exercise I recommend to help you distill your key

messages is called the "two-minute drill." Imagine you had to verbally

present the essence of your entire document in only two minutes. What

would you say? What are the main points that you absolutely would need

to make? These are the key messages that should drive the content of your document.

For each key message, list your supporting points.

If one of your key messages, for example, is "save money on O&M

through different design options," then what do you need to say to

convincingly make your case? Your supporting points generally serve

three primary functions: (1) describe (give clarity), (2) validate (give

proof), and (3) illustrate (give examples). Technical professionals

often over-describe, under-validate, and completely ignore providing

illustrations. At this stage, though, don't worry about the quantity or

balance of your supporting points; list everything you can think of.

Organize your supporting points in descending order of importance. This

applies the old journalistic standard of the "inverted pyramid." Why?

Because most people don't read your documents word for word; they skim.

So you want your most important information up front—in your document,

chapters, paragraphs. Organizing your supporting points at this stage

facilitates your use of the inverted pyramid when you're writing.

Another

benefit of organizing your supporting points is helping you pare down

your content to no more than is needed. My suggestion is to place each

supporting point under one of three headings: (1) what I must say, (2)

what I should say, and (3) what I could say. Many (if not most) of the

points falling in that last category are candidates for the cutting room

floor.

Fit your content outline to the document structure.

To this point you've based your outline on importance rather than the

flow of the document. Now you need to translate it into whatever

document structure is necessary. This can be difficult, but without the

planning steps above you'd be much more likely to omit or obscure your

key messages. Beware of slavish devotion to a traditional document

outline. You may determine that a reorganization is appropriate to

feature your most important content. For example, I favor putting

conclusions and recommendations—your most important information—at the

front of a report rather than the traditional position in the back.

Now you can start writing.

Having built a detailed content outline and fitted it to your document

structure, the writing comes much easier—and the result will be much

better. By the way, this process is even more powerful for team writing

assignments. Rather than the usual divide-and-conquer approach, get your

team together to work through the above planning process. The

collective brainstorming is much more likely to lead to a document that

will get the results you want.

Many (if not most) technical professionals are ineffective writers. That fact is widely acknowledged. The question is does anyone really care? I don't see A/E firms investing much in helping their staff become more proficient writers.

Perhaps they haven't considered the costs of poor writing: Lost proposals, weak marketing, unapproved solutions, project mistakes, client claims, interoffice conflict, lost productivity—to name a few. I have seen all of these over the years as a result of poorly written proposals, reports, contracts, policies, correspondence, emails, or procedures.

On the flip side, strong writing can yield substantial business benefits. I'm hardly a distinguished writer, but I've compiled a 75% proposal win rate over the last 20 years, producing more than $300 million in fees. I helped my previous employer generate millions of dollars in new business that started with prospective clients contacting us because of something we'd written. I wrote letters to regulatory agencies making the case for regulatory exceptions that allowed innovative solutions saving our clients over $18 million.

The business case for strong writing is too compelling to be ignored, although it commonly is in our profession. But you don't have to settle for the status quo. By applying a few principles of what I call Power Writing, you and your colleagues can get the results you've been missing out on. What is Power Writing? It's writing that delivers the desired result. To accomplish that, you need to attend to three basic principles:

Many (if not most) technical professionals are ineffective writers. That fact is widely acknowledged. The question is does anyone really care? I don't see A/E firms investing much in helping their staff become more proficient writers.

Perhaps they haven't considered the costs of poor writing: Lost proposals, weak marketing, unapproved solutions, project mistakes, client claims, interoffice conflict, lost productivity—to name a few. I have seen all of these over the years as a result of poorly written proposals, reports, contracts, policies, correspondence, emails, or procedures.

On the flip side, strong writing can yield substantial business benefits. I'm hardly a distinguished writer, but I've compiled a 75% proposal win rate over the last 20 years, producing more than $300 million in fees. I helped my previous employer generate millions of dollars in new business that started with prospective clients contacting us because of something we'd written. I wrote letters to regulatory agencies making the case for regulatory exceptions that allowed innovative solutions saving our clients over $18 million.

The business case for strong writing is too compelling to be ignored, although it commonly is in our profession. But you don't have to settle for the status quo. By applying a few principles of what I call Power Writing, you and your colleagues can get the results you've been missing out on. What is Power Writing? It's writing that delivers the desired result. To accomplish that, you need to attend to three basic principles:

1. Purpose Driven: Define the Desired Result. As Yogi Berra famously quipped, "If you don't know where you're going, you'll end up somewhere else." Technical professionals often jump right into writing without much planning, or a clear understanding of what it is they're trying to accomplish. Everything you write has a purpose, but the chances are you don't really think about it. You just start writing because you have something to say. Yet simply communicating your message often falls short of getting the result you want.

Power Writing demands a plan, what it is you want to achieve and how that will be facilitated through your writing. At the most basic level, you are typically seeking to do one of three things—inform, instruct, or influence. Each of these broad objectives calls for a different approach to writing. When you're not clear on your purpose, you're more likely to write a proposal that reads like a technical report. Or a report that has no clear objective. Or a work process description that seems to ignore the needs of the people following it.

Once you have your purpose identified, the next step is to determine your Key Messages. These are the 3-5 things that you absolutely must communicate effectively to achieve your purpose. For each Key Message, you then want to define the supporting points that are needed to clarify and validate your point. This process results in a detailed content outline that will guide your writing.

2. Reader Focused: Facilitate Message Reception. Achieving your purpose is ultimately dependent upon your readers. It takes two to have successful communication. I liken it to a forward pass in football. The quarterback must deliver the ball on target, but the receiver has to catch it. If you're like most, your focus as a writer is on making the pass. But you need to give equal attention to making sure it is received.

A good example of this is email. If you send an email to a client or colleague, you may feel you did your job. But if the recipient doesn't read it or misunderstands it, don't you share some responsibility for that outcome? Power Writing isn't just sending out the equivalent of perfect spirals, but delivering it in a way that makes it more catchable.

That happens in several ways. Foremost, you need to try to see the issue from your readers' perspective. Then they'll be more interested in what you have to say. A common disconnect in our industry is approaching a project from a purely technical perspective when the client is more concerned with the business or stakeholder implications. You won't likely accomplish your purpose in writing unless it aligns in some way with what your readers want or value.

Reader-focused writing also means making it user friendly. One of the best ways to do this is to convey your message as efficiently as possible. Did you know it takes the average adult about one hour to read 35 pages of text? You should write with the expectation that it won't be read word for word (yes, even your emails). Make your main points skimmable. Make effective use of graphics. Use words everyone understands. Write in a conversational tone that easily connects.

3. Engages the Heart: Move Your Readers to Act. Of course, not everything you write is intended to spur your readers to action. But the most important writing you do is when you want to influence a particular response. It's unfortunate, then, that technical professionals struggle so much with persuasive writing. A big part of the problem is that they have been taught to write in a manner that is fundamentally nonpersuasive.

Technical writing is by nature intellectual, objective, impersonal, and features-laden. This style of writing—which pervades our profession—avoids personal language, keeps opinions to ourselves, provides more detail than the audience needs, and buries the main selling points in information overload. It may suffice when writing a study report, technical paper, or O&M manual. But it is entirely the wrong approach when you want to persuade clients, regulators, the public, or employees.

To move your readers to act, you need to engage the heart. That's because persuasion is driven by emotion and supported by logic—not the other way around. It is the human spirit that influences and inspires, and there is precious little of it evident in most of the writing we see in our industry. If you want to be more persuasive, let me suggest you start by dispatching the "technicalese" in favor of acknowledging in your writing the humanity in both you and your audience.

I think the power of writing has been grossly undervalued in the A/E industry. So I want to devote the next few posts to explaining in more detail how to become a Power Writer.

My 17-year-old daughter has decided to become an engineer, but she had no idea which engineering discipline to choose. Since I have connections in the profession, I began setting up appointments for her to meet with different kinds of engineers to see which discipline appealed to her most.

We started with the two that I'm most familiar with—civil and environmental. These engineers did a great job selling their specialty, but none really connected with my daughter. Then one of my clients arranged for her to tour the mechanical engineering department at Virginia Tech. The light came on. She came back with an unexpected amount of enthusiasm (after all, like many engineers, she had been mainly drawn to the profession because she was good at math).

What was it that caught her attention? Well, the robotics laboratory was fascinating, of course. But the attraction went deeper. When she visited the previous engineering offices, they inevitably pulled out plan sets to show her their work. They designed things that others built. In the mechanical engineering lab, students designed, built, tested, and refined their work products. It was much more hands-on.

Now I'm not going to suggest that one field of engineering is better than another. That is a personal preference, and all engineering disciplines do valuable work. But I'm convinced there is added benefit in being closely connected with the desired end result. Ultimately, that's what engineers are hired to deliver. Does that mean that engineers must build what they design in order to be more valuable? No, but I do think many engineers could take a more active role in envisioning and shaping the final outcome.

I have several engineer friends who work in manufacturing. In talking to them about their work, the customer is typically a prominent part of the conversation. This is particularly true among those who make products for other businesses. They have a keen understanding of how their products help their customers succeed.

Among the engineers I work with in the AEC industry, not so much. Many of them seem disconnected from the ultimate project outcomes. Why is the client doing this? What is the business result that is needed? When I pose these questions, I'm often disappointed how little many engineers in our business understand the answers.

This problem isn't limited to the engineers, by the way. Architects can also be prone to overlooking the client's desired end results. A common client complaint is that many architects seem to favor form over function, emphasizing aesthetic design values over practical priorities (such as staying within the client's budget!). One of my favorite architects once told me that his first responsibility was to create spaces that maximize functionality. Aesthetics take precedent, he said, only when the client has designated that as a critical function of the building.

So how can we do a better job connecting our work with the outcomes that ultimately drive our projects? If you follow this blog, you no doubt recognize that I've touched on this general theme before. I keep revisiting it because I keep seeing evidence that it is needed. So here are a few recommendations on how to make your work more results oriented:

Uncover the strategic drivers behind your projects. A/E projects typically help clients achieve strategic business or mission goals. Do you know what those are? Can you describe specifically how your design or solution will enable the client to fulfill those goals?

Don't overlook the human dimension of your solutions. People are always the primary benefactors of your projects. Yet many technical professionals tend to be more focused on the technical aspects of the work than how people are affected. When working on a technical problem, be sure to consider the human consequences. Your solution should explicitly address both the problem and how it impacts people.

Learn to describe your work in terms of its ultimate outcomes. I often point to our project descriptions as evidence that improvement is needed in this area. What do they describe? Typically the tasks performed. Sometimes the technical problem. Rarely do I read, in specific terms, of how the project helped the client be successful. The same is often true in our conversations with existing or prospective clients.

Promote greater cross-disciplinary collaboration. One of the most common project delivery problems I encounter is inadequate coordination between disciplines. This is a primary cause of design-related construction claims. But true collaboration across disciplines goes deeper than merely avoiding mistakes. It leverages the different perspectives and strengths of each discipline to deliver a more encompassing, higher value solution—one that looks beyond the details of project execution to achieving the project's ultimate goals.

Follow the project all the way through. Sometimes A/E firms are contracted through construction and even start-up. That enables you to have a more direct role in ensuring the project's ultimate success. But what if the contract ends with the completed design? I urge that you keep in contact with the client, offering advice and answering questions, helping the finished project achieve its stated goals. It's not all that uncommon that design-related problems occur during construction or operation that the design firm is not made aware of. It's best to monitor project progress to the end to be in a position to help and perhaps learn from your mistakes.

The most valuable thing we do in our industry is not engineering and architecture, but helping clients realize their dreams and ambitions. We solve problems that hamper their business performance and create facilities that enable their success. When we get closer to the desired end results, the perceived value of our work increases. Agree or disagree? Do you have other suggestions for how our profession can be more directly involved in delivering business results?

My 17-year-old daughter has decided to become an engineer, but she had no idea which engineering discipline to choose. Since I have connections in the profession, I began setting up appointments for her to meet with different kinds of engineers to see which discipline appealed to her most.

We started with the two that I'm most familiar with—civil and environmental. These engineers did a great job selling their specialty, but none really connected with my daughter. Then one of my clients arranged for her to tour the mechanical engineering department at Virginia Tech. The light came on. She came back with an unexpected amount of enthusiasm (after all, like many engineers, she had been mainly drawn to the profession because she was good at math).

What was it that caught her attention? Well, the robotics laboratory was fascinating, of course. But the attraction went deeper. When she visited the previous engineering offices, they inevitably pulled out plan sets to show her their work. They designed things that others built. In the mechanical engineering lab, students designed, built, tested, and refined their work products. It was much more hands-on.

Now I'm not going to suggest that one field of engineering is better than another. That is a personal preference, and all engineering disciplines do valuable work. But I'm convinced there is added benefit in being closely connected with the desired end result. Ultimately, that's what engineers are hired to deliver. Does that mean that engineers must build what they design in order to be more valuable? No, but I do think many engineers could take a more active role in envisioning and shaping the final outcome.

I have several engineer friends who work in manufacturing. In talking to them about their work, the customer is typically a prominent part of the conversation. This is particularly true among those who make products for other businesses. They have a keen understanding of how their products help their customers succeed.

Among the engineers I work with in the AEC industry, not so much. Many of them seem disconnected from the ultimate project outcomes. Why is the client doing this? What is the business result that is needed? When I pose these questions, I'm often disappointed how little many engineers in our business understand the answers.

This problem isn't limited to the engineers, by the way. Architects can also be prone to overlooking the client's desired end results. A common client complaint is that many architects seem to favor form over function, emphasizing aesthetic design values over practical priorities (such as staying within the client's budget!). One of my favorite architects once told me that his first responsibility was to create spaces that maximize functionality. Aesthetics take precedent, he said, only when the client has designated that as a critical function of the building.

So how can we do a better job connecting our work with the outcomes that ultimately drive our projects? If you follow this blog, you no doubt recognize that I've touched on this general theme before. I keep revisiting it because I keep seeing evidence that it is needed. So here are a few recommendations on how to make your work more results oriented:

Uncover the strategic drivers behind your projects. A/E projects typically help clients achieve strategic business or mission goals. Do you know what those are? Can you describe specifically how your design or solution will enable the client to fulfill those goals?

Don't overlook the human dimension of your solutions. People are always the primary benefactors of your projects. Yet many technical professionals tend to be more focused on the technical aspects of the work than how people are affected. When working on a technical problem, be sure to consider the human consequences. Your solution should explicitly address both the problem and how it impacts people.

Learn to describe your work in terms of its ultimate outcomes. I often point to our project descriptions as evidence that improvement is needed in this area. What do they describe? Typically the tasks performed. Sometimes the technical problem. Rarely do I read, in specific terms, of how the project helped the client be successful. The same is often true in our conversations with existing or prospective clients.

Promote greater cross-disciplinary collaboration. One of the most common project delivery problems I encounter is inadequate coordination between disciplines. This is a primary cause of design-related construction claims. But true collaboration across disciplines goes deeper than merely avoiding mistakes. It leverages the different perspectives and strengths of each discipline to deliver a more encompassing, higher value solution—one that looks beyond the details of project execution to achieving the project's ultimate goals.

Follow the project all the way through. Sometimes A/E firms are contracted through construction and even start-up. That enables you to have a more direct role in ensuring the project's ultimate success. But what if the contract ends with the completed design? I urge that you keep in contact with the client, offering advice and answering questions, helping the finished project achieve its stated goals. It's not all that uncommon that design-related problems occur during construction or operation that the design firm is not made aware of. It's best to monitor project progress to the end to be in a position to help and perhaps learn from your mistakes.

The most valuable thing we do in our industry is not engineering and architecture, but helping clients realize their dreams and ambitions. We solve problems that hamper their business performance and create facilities that enable their success. When we get closer to the desired end results, the perceived value of our work increases. Agree or disagree? Do you have other suggestions for how our profession can be more directly involved in delivering business results?

Want to get something done in the A/E business?

Manage it like a project. That's my standard advice when confronted with

almost any kind of corporate initiative. Need more sales? Make it a

project. Need to increase profitability? Make it a project. Need to

improve client service? Same answer. Projects are what we do best, so

the more we can fit other corporate activities into a similar framework,

the better.

In my last post, I mentioned a study by Accenture

of companies that are among the leaders in providing the "branded

experience" to their customers. The study found that these companies

share two key traits: (1) they have a deliberate process for delivering a

consistently great customer experience and (2) they regularly solicit

customer feedback to determine how they're doing and what they can do

better. The vast majority of A/E firms do neither.

So

in this post, let me focus on the first strategy—managing the service

delivery process. When it comes to providing great client service, the

vast majority of firms simply rely on their good people doing the right

thing for the client. There's no planning, little process, few

standards, no metrics. We would never entrust our technical work

products to such an unstructured approach. Why? Because the results

would be wildly inconsistent.

And

that's what most firms get with their service delivery. Some

individuals have strong client skills and consistently delight their

clients. Others fail to provide clients the personal attention and

responsiveness they expect, focusing instead on the technical aspects of

the work. The only way to provide consistently good service is to

manage it. Like a project.

Granted,

not all aspects of client service are manageable. You have to have

decent interpersonal skills and a genuine concern for the client (no

process can overcome the lack of these!). But we can still plan, design,

implement, and measure important dimensions of the client experience,

just like the technical components of our projects:

Want to get something done in the A/E business?

Manage it like a project. That's my standard advice when confronted with

almost any kind of corporate initiative. Need more sales? Make it a

project. Need to increase profitability? Make it a project. Need to

improve client service? Same answer. Projects are what we do best, so

the more we can fit other corporate activities into a similar framework,

the better.

In my last post, I mentioned a study by Accenture

of companies that are among the leaders in providing the "branded

experience" to their customers. The study found that these companies

share two key traits: (1) they have a deliberate process for delivering a

consistently great customer experience and (2) they regularly solicit

customer feedback to determine how they're doing and what they can do

better. The vast majority of A/E firms do neither.

So

in this post, let me focus on the first strategy—managing the service

delivery process. When it comes to providing great client service, the

vast majority of firms simply rely on their good people doing the right

thing for the client. There's no planning, little process, few

standards, no metrics. We would never entrust our technical work

products to such an unstructured approach. Why? Because the results

would be wildly inconsistent.

And

that's what most firms get with their service delivery. Some

individuals have strong client skills and consistently delight their

clients. Others fail to provide clients the personal attention and

responsiveness they expect, focusing instead on the technical aspects of

the work. The only way to provide consistently good service is to

manage it. Like a project.

Granted,

not all aspects of client service are manageable. You have to have

decent interpersonal skills and a genuine concern for the client (no

process can overcome the lack of these!). But we can still plan, design,

implement, and measure important dimensions of the client experience,

just like the technical components of our projects:

- Plan. The starting point is to uncover

what the client expects in terms of the working relationship. Such

expectations are rarely explicit in the contract or scope of work, yet

they strongly influence the client's experience.

- Design. Understanding the client's expectations, you then determine what actions are needed to meet or exceed them.

- Implement. Knowing is one thing, doing is

another. Most firms need healthy doses of support and encouragement to

raise service levels. Support can involve training, resources, and

holding people accountable.

- Measure. The most important measurement is

getting periodic feedback from clients. The basic questions: How are we

doing? What can we do better?

Let's break that process out in some more

detail. Below is a basic service delivery process that I've used with

many clients. Not every client is receptive (nor deserving) of such a

structured approach, but for those who are (usually your best clients),

this can be a definitive competitive advantage.

1. Benchmark Expectations

Uncovering

your client's hidden expectations is the foundation of managing the

service delivery process. Service benchmarking involves meeting with the

client at the outset of the project to establish mutual expectations

for the working relationship. The discussion should address issues such

as communication, decisions and client involvement, information and

data, deliverable standards, invoicing and payment, management of

changes, and performance feedback. You might find the Client Service Planner useful for this purpose.

2. Identify Gaps

The

focus of this process is meeting the unique expectations of your

client. So having completed the benchmarking step, the next activity is

to identify where what the client wants varies significantly from what

you normally do. This assessment should take into account both the

standard practices of the firm and the respective project manager or office.

3. Create Service Deliverables

The

next step is to create "service deliverables" to close the gaps

identified. This means treating the delivery of service like the

delivery of any other work product, as mentioned above. Producing

service deliverables involves defining a discrete set of tasks that can

be assigned, scheduled, budgeted, tracked, and closed like any other

project task. This moves service delivery from the realm of the ethereal

to the realm of the manageable. Some additional guidelines:

- Give special attention to those requiring

significant resources or coordination. Focus on those involving multiple

responsible persons or significant costs, or those with potential to

impact the project schedule.

- Alert the client of the costs of special deliverables.

Don't automatically acquiesce to every request the client may make if

there are substantial costs or difficulties associated with satisfying

the request. Explain the added costs (in terms of budget, time, etc.)

and let the client decide if he or she is willing to assume them. Look

for other satisfactory alternatives where appropriate.

- Don't commit to what you cannot deliver. While

this seems obvious, there are many PMs, who in their zeal to please the

client, make promises that they are unlikely able to keep. The old adage

"under-promise and over-deliver" is still good advice.

4. Prepare a Service Plan

The client service plan provides direction for the project team on how service deliverables

will be handled in the context of the project. Preparing such a plan

recognizes that client service involves time and resources like other

project tasks, and should be managed accordingly. This plan is typically

brief and is integrated into the overall project management plan (in most cases, the completed Client Service Planner will suffice).

Since the quality of service deliverables

is much more subjective than technical work products, it's especially

important to secure the client's endorsement of the client service plan.

Confirm that the planned service deliverables

fully meet the client's expectations. Delivering great service is

largely dependent on the client doing his or her part in making the

relationship work. The plan provides a blueprint for key aspects of that

relationship, and involves both parties meeting the obligations

established in it.

5. Implement the Service Plan

The preceding

steps of the service delivery process alone will set your firm apart

from all but a few. But these activities ultimately accomplish nothing

if there is inadequate follow-through. Your commitment to the branded

experience obviously must extend beyond the planning stages to the point of

delivery. This involves not just implementing the service plan, but

being responsive to the client's evolving needs and expectations through

the course of the project.

The over-arching goal: Make every client encounter (every touchpoint) a positive experience.

6. Solicit Client Feedback

Getting

regular feedback from your clients is critical to ensuring that you are

meeting expectations. Two primary means are recommended: (1) ongoing

dialogue with the client and (2) periodic formal survey. I outlined a general approach to this in a previous post.

By

the way, service sells. Not unsubstantiated claims that "we listen" or

"we give personal attention." But if you describe the above process in a

sales call, proposal, or shortlist presentation, you will immediately

set your firm apart.

I've

seen it be a major factor in winning large contracts. One such client, a

major airline, responded in the interview: "Why is no one else talking

about this? The reason we're replacing five of our six current

consultants is we're not happy with their service. Yet you are the only ones to tell us how

you will serve us better."

Finally, let me close by summarizing the three basic advantages of a service delivery process:

- Managing service delivery like other project tasks puts it more in the realm of the familiar

- It enables you to provide a more consistent level of service across the organization

- It converts client service into a more tangible (you can draw it) value proposition

Could this be your best unexploited opportunity to differentiate your firm? Test drive it with a few of your clients and see for yourself.

At the core of your firm's brand is what the client experiences working with your firm. So how much time and money do you spend on enhancing the quality of the client experiences you deliver? If you're like the overwhelming majority of A/E firms, it pales in comparison to the investment made in your technical capabilities. So here's a golden opportunity to differentiate your firm: Deliver what is known as the branded experience.

What is the branded experience? The most helpful definition I've found comes from the Forum Corporation. They describe the branded experience as one characterized by four basic qualities: (1) it's consistent, (2) it's intentional, (3) it's differentiated, and (4) it's valued. Notice that the first two characteristics are dependent on the service provider; the second two are discerned by the customer. The branded experience involves a sort of informal partnership between the two parties.

Accenture conducted a study to determine what separates the companies that deliver the branded experience from the rest. The study found that the best companies did two important things:

At the core of your firm's brand is what the client experiences working with your firm. So how much time and money do you spend on enhancing the quality of the client experiences you deliver? If you're like the overwhelming majority of A/E firms, it pales in comparison to the investment made in your technical capabilities. So here's a golden opportunity to differentiate your firm: Deliver what is known as the branded experience.

What is the branded experience? The most helpful definition I've found comes from the Forum Corporation. They describe the branded experience as one characterized by four basic qualities: (1) it's consistent, (2) it's intentional, (3) it's differentiated, and (4) it's valued. Notice that the first two characteristics are dependent on the service provider; the second two are discerned by the customer. The branded experience involves a sort of informal partnership between the two parties.

Accenture conducted a study to determine what separates the companies that deliver the branded experience from the rest. The study found that the best companies did two important things:

- They had a formal process for consistently delivering the branded experience

- They rigorously solicited customer feedback to determine what customers want

Notice the alignment between Accenture's and Forum's research? Companies that have a delivery process are intentional and able to provide consistent customer experiences. Those that regularly solicit feedback can determine what customers think is different and what they value.

So how are we doing in our industry? Over the years, I've polled hundreds of firms on this topic at events where I've spoken. I've yet to find a firm that has a true client experience delivery process (other than firms I've worked with). I'm sure there are a few out there, but they are rare. Only about one in four firms I've polled have a formal process for client feedback. The company behind the Client Feedback Tool claims that only 5% of A/E firms collect client feedback regularly.

In my research of differentiation strategies for professional service firms, delivering the branded client experience is at or near the top of the list. This reflects a general trend in business, popularized by the book The Experience Economy. The most distinctive and successful brands across multiple industries generally provide great customer experiences. There's certainly evidence within our own industry that clients place a higher value on the experience that we have typically acknowledged.

So how is your firm doing in delivering the branded experience? The graphic below, adopted from the Forum Corporation, is a handy way to assess where you stand in the service-level progression leading to the branded experience:

Random experience. At this level, the customer experience is neither consistent or intentional. It varies from one time to another depending on which individual service provider you work with, which office or department, or what service or product you received. In other words, it's like working with many A/E firms. One project manager is very attentive, the next seemingly indifferent. One office provides great quality work products, another not so good.

Predictable experience. At this level, the experience is pretty consistent because the provider has taken steps to make it so. But it is either not significantly different from what you could get elsewhere or the difference isn't that valued by most customers, or both. I call this the Golden Arches Experience. The one thing McDonald's has going for it is that the food, service, and atmosphere are pretty consistent whichever of their 14,350 restaurants in the U.S. you visit. But that's also what's working against them!

Branded experience. When you reach this level, you're consistently delivering an experience that customers value. You don't get here simply because you've got good people working for you. It requires intentional effort. It requires a reliable experience delivery process. And it requires regularly asking clients what they really want, and how you can do better. There are many good A/E firms out there, and clients are generally satisfied. But the opportunity remains for your firm to distinguish itself because it commits to the high standard of the branded experience.

Can you really package the delivery of professional services into some kind of consistent process? That's the question I plan to answer in my next post.

What's necessary to build

sustainable business success? Lasting client relationships. Imagine if

you never had any repeat business. Could you survive? Highly unlikely.

So keeping existing clients deserves every bit the focus that finding new ones does.

It's

interesting, then, that most firms pay substantially more attention to

winning new clients than taking care of their current ones. If you doubt that conclusion, consider these questions:

How much of your strategic plan is devoted to improving business

development compared to improving client care? Do you have a sales

process, but not a relationship building process? Which receives more of

your training budget? Or more discussion in staff meetings?

Obviously, there's

nothing wrong with giving emphasis to business development. In fact,

most firms could stand to give it more. But let's not overlook the fact

that the best way to grow your business is usually through existing

client relationships. Are you taking steps to make those relationships

stronger? Here are five suggestions to do just that:

1. Create a client relationship building process.

You probably have a few individuals in your firm who are skilled at

nurturing strong client relationships. And some who aren't. Therein lies

the problem—a crucial function that's left to individual competency and

initiative. You don't manage projects that way; there are standard

procedures to ensure some measure of consistency. In fact there are many

less critical activities in your firm that have been defined as a

repeatable process.

So

why not an approach for building client relationships? Of course, there

are interpersonal dynamics in relationships that are not easily

programed. But if marriages can be strengthened by applying generic tips

from a book or conference, such improvements can certainly be realized

with clients. The key is to define certain elements of relationship

building that lend themselves to being replicated across the

organization. Here's how to get started:

What's necessary to build

sustainable business success? Lasting client relationships. Imagine if

you never had any repeat business. Could you survive? Highly unlikely.

So keeping existing clients deserves every bit the focus that finding new ones does.

It's

interesting, then, that most firms pay substantially more attention to

winning new clients than taking care of their current ones. If you doubt that conclusion, consider these questions:

How much of your strategic plan is devoted to improving business

development compared to improving client care? Do you have a sales

process, but not a relationship building process? Which receives more of

your training budget? Or more discussion in staff meetings?

Obviously, there's

nothing wrong with giving emphasis to business development. In fact,

most firms could stand to give it more. But let's not overlook the fact

that the best way to grow your business is usually through existing

client relationships. Are you taking steps to make those relationships

stronger? Here are five suggestions to do just that:

1. Create a client relationship building process.

You probably have a few individuals in your firm who are skilled at

nurturing strong client relationships. And some who aren't. Therein lies

the problem—a crucial function that's left to individual competency and

initiative. You don't manage projects that way; there are standard

procedures to ensure some measure of consistency. In fact there are many

less critical activities in your firm that have been defined as a

repeatable process.

So

why not an approach for building client relationships? Of course, there

are interpersonal dynamics in relationships that are not easily

programed. But if marriages can be strengthened by applying generic tips

from a book or conference, such improvements can certainly be realized

with clients. The key is to define certain elements of relationship

building that lend themselves to being replicated across the

organization. Here's how to get started:

- Identify common traits among your best client relationships

- Determine the steps that were taken to build those relationships

- Develop a relationship building process based on your assessment

- Pilot this process with a few clients with growth potential

2. Clarify mutual expectations.

For every project, you develop a scope of work, schedule, and budget

that the client reviews and approves. But many aspects of the working

relationship—such as communication, decision making, client involvement,

managing changes, and monitoring satisfaction—are not discussed and

explicitly agreed upon with the client. In my experience, most service breakdowns are

caused by unknown or misunderstood expectations.

To

delight clients and win their loyalty, you need to know how they like

to be served. Over time this becomes clearer, but you may not make it

that far. How much better to simply ask what the client's expectations

are up front, as well as to share what you'd like from the client in return to make the relationship stronger? This is a practice I call "service benchmarking," and you may find my Client Service Planner helpful in this regard.

3. Increase client touches.

These are simply the direct and indirect interactions you have with

clients. Too often these touches are limited to times of necessity. This

is the project manager who only calls when there's a problem. Or the

principal who is out of sight until the next RFP approaches. Clients

notice. Perhaps the biggest complaint I've heard in the many client

interviews I've conducted is the failure of A/E firms to communicate proactively.

What are some ways to increase client touches? Consider the following:

- Invite the client to your project kickoff meeting

- Send monthly project status reports

- Share internal project meeting minutes and action items

- Call to discuss issues before they become problems

- Send articles, papers, reports,and tools of interest to the client

4. Periodically seek performance feedback. Having clarified expectations in advance, it's important to check in on occasion

to ask how well you're doing. The frequency and timing of these

discussions is hopefully one of the expectations you established during

the benchmarking step. This is another valuable way to increase client

touches.

About 1 in 4 firms in this business formally solicit client feedback, and reportedly only about 5

percent do it regularly. So there's a tremendous opportunity for you to

distinguish your firm with your clients. Here are some tips for getting

effective feedback:

- Have someone not directly involved in the project do this

- Mix both discussions and a standard questionnaire

- Talk to multiple parties in the client organization if possible

- Be sure to follow up promptly to any concerns identified

5. Don't disappear between projects.

This relates back to my advice about client touches; don't limit them

only to when it's in your self interest. Keep in touch with the client

after the project is completed—for the client's sake. For one thing, the

real value of your work isn't realized until the facility you designed

is put into operation or the recommendations in your report are acted

upon. You want to be talking with the client when these moments of

truth happen, whether it's part of your contract or not.

Offer

whatever support you can to further ensure the project's success. But

you also want to demonstrate your interest in the client's success

outside the project. Provide helpful information and advice, in person,

over the phone, and digitally (as part of your content marketing effort).

The time between projects (assuming you've won the client's trust to do

another project together) can be a productive relationship building

time, because it's often unexpected. Having met the client's

expectations during the project, this is another chance to exceed them.

In my last post I argued that all project managers should be contributing to their firm's sales efforts. Only half do, according to the Zweig Group. A prominent reason for the low participation is that most PMs don't feel competent or comfortable in this role (and this is also true of many who are involved in sales!). As I wrote previously, I'm confident that capable PMs can successfully transfer their project management skills to selling—it's much the same skill set. Here are some suggestions for helping them make that transition:

Train them in a service-centered approach to selling. The problem most PMs have with selling is that they have an overwhelmingly negative impression of salespeople. They have their own experiences as a buyer, and that taints their view of selling. But rather than avoid selling, they should be striving to change the experience for those who buy the firm's services. Serve prospective clients rather than sell to them.

"High-end selling and consulting are not different and separate skills," observes sales researcher Neil Rackham, "When we are watching the very best [seller-doers] in their interactions with clients, we cannot tell whether they are consulting, selling, or delivering." For the A/E professional, this means uncovering needs, offering advice, recommending solutions—giving a meaningful sample of what it will be like working together under contract. This kind of approach takes the sting out of selling for both the PM and the client.

In my last post I argued that all project managers should be contributing to their firm's sales efforts. Only half do, according to the Zweig Group. A prominent reason for the low participation is that most PMs don't feel competent or comfortable in this role (and this is also true of many who are involved in sales!). As I wrote previously, I'm confident that capable PMs can successfully transfer their project management skills to selling—it's much the same skill set. Here are some suggestions for helping them make that transition:

Train them in a service-centered approach to selling. The problem most PMs have with selling is that they have an overwhelmingly negative impression of salespeople. They have their own experiences as a buyer, and that taints their view of selling. But rather than avoid selling, they should be striving to change the experience for those who buy the firm's services. Serve prospective clients rather than sell to them.

"High-end selling and consulting are not different and separate skills," observes sales researcher Neil Rackham, "When we are watching the very best [seller-doers] in their interactions with clients, we cannot tell whether they are consulting, selling, or delivering." For the A/E professional, this means uncovering needs, offering advice, recommending solutions—giving a meaningful sample of what it will be like working together under contract. This kind of approach takes the sting out of selling for both the PM and the client.

Budget time specifically for sales. The other big excuse for why PMs don't sell is that there isn't enough time. Or more specifically, that spending time developing new business subtracts from time on billable project work. Given the obsession with utilization that exists in many firms, it's hardly surprising that this perception is so prevalent. But the claim is seldom supported by the facts.

Nearly all PMs work a substantial number of nonbillable hours, a portion of which could be devoted to sales activities. The problem is that these hours are rarely budgeted or managed, so that in effect selling is done with leftover time. And who has surplus time left over? You can minimize the concern that selling displaces billable hours by managing your business development efforts like project work, including budgeting a portion existing nonbillable hours for this purpose.

Fit sales responsibilities to PMs' individual strengths. Selling is not as monolithic an activity as many presume, nor does it favor a specific personality type. There is a potential sales role for virtually anyone in your firm, including your PMs. Some are comfortable at networking functions, others better at one-on-one conversations. Some are big-picture strategists, others more analytical problem solvers. Some are competent writers, others better in communicating verbally. Some may be capable in making sales calls, others are better assigned to doing research, writing proposals, or developing solutions. The key is fitting the right people to the right roles.

PMs often claim that they don't have the personality to sell. But the research finds no real correlation between personality type and sales success. Fit, again, is the critical strategy. Help PMs shape their sales responsibilities around both their capabilities and their personality.

Bolster your marketing efforts.

Technical professionals typically struggle more in starting the sales process than in closing the sale. They often dislike prospecting for new

leads, especially making cold calls, attending networking events, and initiating client relationships.

Effective marketing can shorten the sales cycle by bringing interested

prospects to your door. Most PMs are much more comfortable picking up

the sales effort at this point.

Where

to start? Consider the marketing tactics that have proven most effective for professional service firms. These activities typically

require significant support from the firm's content experts, which

likely will include at least some of your PMs. They don't want to make cold

calls or work the room? How about giving a presentation, helping write

an article, or contributing to a seminar? Involvement in marketing not only

builds the firm's brand, but the personal brands of your PMs—making it

easier for them to sell.

Increase collaboration. Selling is often a lonely activity, which further magnifies the discomfort most PMs have with it. That's why I favor building your sales team, where those involved in sales regularly meet together, share information, encourage one another, plan sales pursuits, and hold each other accountable. Have members of the team work together on sales calls when that makes sense. The investment you make in promoting collaboration, in my experience, will more than pay off in increased sales productivity.

Provide ongoing coaching. Sales coaching can dramatically improve results for your PMs engaged in selling. If you do training, as suggested above, you'll need to reinforce it to make it successful—meaning real-time feedback and instruction. Organizing your sales team can provide opportunities for peer-to-peer coaching. Pairing up PMs with your best sellers is another option. Or you may decide to seek outside support from a consultant. A good coach helps build both the PM's capabilities and motivation in the most effective manner—on the job.

Being a project manager is a tough job. I get that. PMs are charged with keeping the client happy, delivering a technically sound solution, meeting the budget and schedule, coordinating the project team, interacting with multiple project stakeholders, ensuring the quality of deliverables, and often a myriad of other management, supervisory, and administrative duties outside of their project work.

Did I mention business development? Is it fair to add that responsibility to an already long to-do list? According to a Zweig Group survey, only 4% of PMs claimed no involvement in BD activities. Over 80% indicated they contribute to proposals, 60% make presentations, and 55% participate in sales activities. That last number surprises me. I think it should be closer to 100%.

I can hear the howls of disapproval. Numerous PMs have told me they don't have the time or the personality or the desire to get involved in selling. Many firms seem to concur, putting little if any pressure on PMs to actively support sales activities. But there are several reasons why I believe PMs are needed to have a truly successful sales process:

Being a project manager is a tough job. I get that. PMs are charged with keeping the client happy, delivering a technically sound solution, meeting the budget and schedule, coordinating the project team, interacting with multiple project stakeholders, ensuring the quality of deliverables, and often a myriad of other management, supervisory, and administrative duties outside of their project work.

Did I mention business development? Is it fair to add that responsibility to an already long to-do list? According to a Zweig Group survey, only 4% of PMs claimed no involvement in BD activities. Over 80% indicated they contribute to proposals, 60% make presentations, and 55% participate in sales activities. That last number surprises me. I think it should be closer to 100%.

I can hear the howls of disapproval. Numerous PMs have told me they don't have the time or the personality or the desire to get involved in selling. Many firms seem to concur, putting little if any pressure on PMs to actively support sales activities. But there are several reasons why I believe PMs are needed to have a truly successful sales process:

PMs are the primary contacts with clients. Or at least they should be. PMs are typically the ones who work closest with clients on projects. I've seen situations where principals or department heads assumed this role, but it's less than ideal. In interviewing hundreds of clients over the years, it's clear that the overwhelming majority favor strong PMs who take charge of ensuring project success and serve as the primary liaison with the client and other stakeholders. This role alone makes PMs the logical choice to support the firm's sales efforts.

PMs are one of the critical assets you are selling. You can try to sell the firm's qualifications, but most clients want to know about the individuals who specifically will be working on their project. Chief among these project team members is the PM. Who can best sell the PM's strengths to the client? The PM, ideally. Not by telling, but by demonstrating. The nature of professional services is that we sell the people who perform the services. And the person who most needs to gain the client's confidence, in most cases, is the PM.

Selling should be about serving. I've encountered many PMs who were reluctant to sell to existing clients because they feared it might taint the project relationship. I understand their concern, if you look at it through the lens of traditional selling. But the most effective way to develop new business with clients in the A/E business is not by pushing your services. It's about serving—about meeting needs, providing advice, identifying solutions. If PMs really care about their relationship with clients, they should be looking for other ways to help.

PMs have the right skill set for selling. If you accept my previous point that serving clients is the best way to "sell," then it follows that PMs (good ones, at least) are particularly suited for this task. Who better to help clients? Strong PMs generally are more effective at bringing a broader, multidisciplinary perspective to the project than the technical practitioners who will make up the rest of the project team. PMs should have client skills that readily transfer to a service-centered approach to sales.

Despite claims to the contrary, the skill set for project management is much the same as for selling in this manner: Interpersonal skills, communication, problem solving, planning, collaboration, follow-through, etc. Any PM who cannot sell is probably not very good at project management either. And the claim that they don't have the personality? Research shows no correlation between personality and sales success.

Participation in sales increases a sense of ownership. There's something about building a relationship from scratch with a client that engenders a deeper sense of ownership of that relationship. My observation is that PMs who are actively involved in selling are generally more committed to keeping clients happy. Perhaps that's because they engaged the client before the relationship could be mistaken as simply completing a scope of work.

At a minimum, I think it's critically important to involve the PM in defining the proposal strategy, winning the shortlist interview, and negotiating the contract. PMs should always be involved in determining the scope, schedule, and budget of the project—they shouldn't be asked to deliver something they had no part in defining.

Agree or disagree? I'd love to hear what you think about the PM's role in sales. Next post I'll offer some suggestions for helping PMs succeed in selling.

Those appointed boss usually feel empowered. I felt intimidated—and that ultimately made me a better leader. When I was asked to step into the branch manager role for a 35-person office, I was leaping over several people on the organization chart that I considered my senior. One was a principal in the firm (and the former branch manager).

I couldn't envision myself telling these people what to do. Instead, I would need to persuade and inspire them. In other words, I would need to be more leader than boss. It worked. The office performed very well and was an incubator for several operational innovations (thanks to my dual role as leader of our corporate quality and service improvement initiative).

Those appointed boss usually feel empowered. I felt intimidated—and that ultimately made me a better leader. When I was asked to step into the branch manager role for a 35-person office, I was leaping over several people on the organization chart that I considered my senior. One was a principal in the firm (and the former branch manager).

I couldn't envision myself telling these people what to do. Instead, I would need to persuade and inspire them. In other words, I would need to be more leader than boss. It worked. The office performed very well and was an incubator for several operational innovations (thanks to my dual role as leader of our corporate quality and service improvement initiative).

That experience reinforced my convictions about leadership, that the real power is held by those you lead. Sure, you can force them into compliance. You're the boss! But you cannot make them give you their best efforts. That comes only voluntarily. Your role as leader is to evoke their want-to rather than enforce their have-to.

Much has been written in recent years about employee engagement. Studies show that an engaged workforce produces greater profit, growth, shareholder value, quality, innovation, customer service, and loyalty to the company. These results flow in large part from discretionary effort, employees willingly going beyond what is required to deliver more of what is possible.

Leaders induce discretionary effort; bosses extract compliant effort. Leaders motivate; bosses mandate. All else being equal, employees who want to follow you will always outperform those who have to. That's why converting bosses into leaders is so important for any firm. Here are some steps you can take to further make that transition:

Prefer asking over telling. We teach our young children the value of asking nicely then sometimes forget the lesson when stepping into a position of authority. The principle still applies in the workplace. But there's another reason to master asking good questions...

Seek advice as much as you give it. The most successful leaders never stop learning, so they don't hesitate to ask others for insight. That includes their employees. The strength of working in an organization is the variety of perspectives, experiences, and talents available. But these assets need to be effectively tapped, which strong leaders do by empowering others and seeking their input.