Content is king in marketing professional services. Yet most A/E firms are content poor. They don't produce enough articles, papers, presentations, webinars, and the like to sustain an effective content marketing effort.

But there is a fallback position to fill in the gaps in your marketing output: Other people's content. Although I produce significant content of my own, I rely heavily on that produced by others to support both my marketing and my consulting practice. The internet makes it easy to find, store, and share this information.

Let me suggest that you also adopt the practice of hoarding content for your firm. In this post, I'll discuss why you should and how to go about it:

The Value of Content

Content in the form or writing or presentations constitutes a portable and readily sharable expression of your expertise. The best content is that most relevant and helpful in addressing client needs. Content extends your consulting practice by providing advice and information that the client can consume at his or her own convenience. It also makes a great way to introduce a prospective client to your firm.

Content is king in marketing professional services. Yet most A/E firms are content poor. They don't produce enough articles, papers, presentations, webinars, and the like to sustain an effective content marketing effort.

But there is a fallback position to fill in the gaps in your marketing output: Other people's content. Although I produce significant content of my own, I rely heavily on that produced by others to support both my marketing and my consulting practice. The internet makes it easy to find, store, and share this information.

Let me suggest that you also adopt the practice of hoarding content for your firm. In this post, I'll discuss why you should and how to go about it:

The Value of Content

Content in the form or writing or presentations constitutes a portable and readily sharable expression of your expertise. The best content is that most relevant and helpful in addressing client needs. Content extends your consulting practice by providing advice and information that the client can consume at his or her own convenience. It also makes a great way to introduce a prospective client to your firm.

There has been much written about content marketing (including in this space). But I want to point out other advantages to collecting valuable content, including:

- Build your reputation as a thought leader in your field. This is the classic role of content marketing, yet something still all too uncommon among A/E firms.

- Strengthen relationships with existing clients. Regularly sending useful information and advice reminds customers that you're thinking about them and looking for ways to help.

- Keep in front of prospective clients. There are only so many times you can call upon a prospect without wearing out your welcome. Helpful content is a great way to remain visible without imposing too much.

- Educate yourself. The best professionals are constantly learning and growing, and the practice of hoarding content can be a natural outgrowth of their ongoing research.

- Compile a resource library. Finding the best information takes time, so why not store that source or link in a place where you can readily find it again? Content hoarders should be intent on building their own customized electronic library (see below).

The more content you have and the more easily accessible it is, the greater its value will be to your business. In the internet age, there's no lack of information. The challenge is sorting through the glut of content that is of little value and finding those nuggets of insight that are worth sharing and filing away for future use. Most don't take the time or have the discipline to do this. That's what makes it all the more valuable when you do. It can be a competitive advantage.

How to Compile and Use Content

So where do you start? Here are some tips on becoming a content hoarder:

Identify your target audiences. For firms that focus on a few core markets, this will be easier than for those working across multiple markets. If your firm falls in the latter category, the task of collecting helpful content becomes more difficult. Unless you can assemble the manpower to compile content in multiple markets, I recommend narrowing your effort to just a few. The more specific the content is to particular businesses, the more useful it will be perceived by clients.

Don't make the mistake of collecting content relative to your business and services to the neglect of your clients' businesses. Sure, an article on BIM can appeal to facility managers in multiple markets. But if it is specifically written for managers in your client's business, it will likely be more appreciated. On the other hand, you don't want to miss opportunities to share content across markets when it's appropriate.

Stay abreast of what matters most to your clients. As I wrote previously, there is great value in connecting whatever you do to meeting your clients' strategic needs. This is also true in how you share content. Judge the value of the content you produce, collect, and share from the client's perspective, not your own. Determine what to share based on how useful it will be to your audience, not on how well it promotes your area of specialization. That means you need to ask questions that stray outside your expertise on occasion to understand what matters most to your clients. That in large part defines the value of the content you share.

Create your storage and filing system. The internet is my go-to source for valuable content for obvious reasons. There's an endless supply of information and advice—when you can find it—and providing an internet URL is the simplest way to share content with others. Even materials I develop for non-internet uses eventually get posted on my website if it's something I envision sharing often with customers and followers.

If your content is predominantly web-based, the quickest way to file it is as bookmarks in your browser. As with any filing system, you want to plan for the optimum organization of your collected content in a hierarchy of folders. But you also have the advantage of being able to search your bookmarks by specific search terms (the means of doing this varies by browser).

If your content covers a variety of formats such a text, web links, photos, and audio, using a note-taking app like OneNote or Evernote is highly recommended. Once again, your compilation can readily be searched to find what you're looking for.

Develop a plan for using content in your marketing. Many A/E firms define marketing strategy only vaguely, and sometimes ignore the specifics of content sharing even if they do have a marketing plan. Your plan should include monthly goals for leveraging content—both that created and collected by your firm—in your marketing activities. Use multiple channels for maximum impact. Be sure to center your social media efforts on sharing content.

Track content-sharing touchpoints in your appointment calendar. This refers to those times when you share targeted content with a client or prospect, something that you want to become an ongoing practice. Often this will be prompted by a recent or upcoming conversation, or perhaps a new development in the project or pursuit. But you also want to account for those times when a client touchpoint is not prompted by circumstances, when it's easy to neglect staying in touch with the client because your attention is diverted elsewhere. That's where you need to make and keep appointments, set at intervals you think are appropriate to maintain the relationship.

When you find something interesting, always consider who might appreciate your sharing it. This is a good measure of how focused you are on your clients and others in your network. Not just those with whom you're currently working, but past and prospective clients with whom you're not actively engaged. It takes only a moment longer to consider who else might find that news item, white paper, or video of value.

You might find it helpful to keep a list of those individuals with whom you particularly want to stay in touch. When you find interesting content, review the list and identify those who might appreciate your sending it. Don't limit this practice to clients, but include others in your network who might be instrumental in helping your firm win or perform that next big project.

A few other examples of how I use my storehouse of content that might inspire you to do something similar:

- Look for ideas and information for blog posts, articles, or webinars I might prepare

- Compile the best content I find in a monthly ezine to hundreds of clients and prospects

- Send to publishers, conference chairs, and association leaders looking for ideas for articles, seminars, conference sessions, or webinars

- Send as a follow-up to participants in my training workshops or conference sessions, usually compiled in a professional-looking email

- Research for upcoming consulting assignments, always looking for fresh ideas and best practices

Content is king, and not just for marketing purposes. You probably already discover a lot of it in your business web searches. Maybe it's time to start hoarding it so you can make better use of it.

In my last post I introduced the Service Continuum, the idea that identifying and satisfying needs should characterize your interactions with clients both before and after the sale. This philosophy is well supported by the facts: Serving prospective clients is the best way to win their business. And for professionals, that service-centered approach to selling inevitably involves sharing information and advice.

But the notion of giving away expertise for free causes consternation for many in the A/E industry. This reluctance has existed since I first entered the business in 1973, and probably before that. If you're sharing your expertise for nothing, the reasoning goes, that's bound to devalue your services. Perhaps that fear helps explain why our industry has been slow to embrace consultative selling and content marketing—the two prevalent business development trends in professional services.

Does offering free advice through your sales conversations and marketing, in fact, devalue your services? I would argue it does quite the opposite. Here are the reasons I offer to support my conclusion:

In my last post I introduced the Service Continuum, the idea that identifying and satisfying needs should characterize your interactions with clients both before and after the sale. This philosophy is well supported by the facts: Serving prospective clients is the best way to win their business. And for professionals, that service-centered approach to selling inevitably involves sharing information and advice.

But the notion of giving away expertise for free causes consternation for many in the A/E industry. This reluctance has existed since I first entered the business in 1973, and probably before that. If you're sharing your expertise for nothing, the reasoning goes, that's bound to devalue your services. Perhaps that fear helps explain why our industry has been slow to embrace consultative selling and content marketing—the two prevalent business development trends in professional services.

Does offering free advice through your sales conversations and marketing, in fact, devalue your services? I would argue it does quite the opposite. Here are the reasons I offer to support my conclusion:

The internet has forever changed how clients buy. In the old days of selling, rainmakers were the primary conduit of information about service providers and their services. Now the internet serves much of that function. According to one study, 78% of executive buyers use the internet to search for information about professional service providers. Eighty-five percent say that what they find online influences their buying decisions. Another study of B2B buyers found that about 60% of the buying decision process is now performed online before they start talking with salespeople.

Showing beats telling hands down. The above findings make it clear that having a good website is important. Indeed, three in four buyers say the quality of a firm's website influences their decision. But don't overestimate the value of the self-promotional content that fills the typical A/E firm website and other marketing vehicles. Buyers prefer helpful content over sales copy, and expert advice over self-advocacy.

Consultant David Maister told the story of when he needed legal help with a probate matter. He was referred by friends to three law firms with expertise in that area. The first two firms he talked to expounded on their qualifications. An attorney with the third firm said little about his firm, but focused questions on Maister's needs and understanding of the issue. He offered to send Maister a checklist that would guide him through the process—what steps are needed, who to contact, and when he would need legal help.

Which firm do you think he hired? Not necessarily the most qualified, but the most helpful. Are buyers of your services any different?

Helping buyers builds trust. This is a huge issue in professional services because our services are more personal, strategic, and potentially risky than most. Thus building trust is your most important task in advancing the sales process. Yet selling is among the most distrusted professions. Why? The perception of self interest on the part of the seller.

When you sell instead of serve, you help confirm the suspicion that you're primarily looking out for your own interests. On the other hand, focusing on the client, helping solve problems, and providing helpful information and advice demonstrates concern for the buyer—the most important trust-building dimension for professional service sellers.

Trust clearly adds value to what you do. When you enable the prospect to sample your services by sharing your expertise, you remove some of the uncertainty from the buying decision. You get the chance to show your value instead of just talking about it.

Sharing expertise helps build your reputation. A survey of A/E/C service buyers by Hinge found that the most important selection factor was the firm's reputation. So how do you build a reputation that factors into the buying decision? Other than referrals or previous experience with the client, the obvious way is through your marketing. So tell me: Does touting your credentials or sharing your insights build a strong reputation?

When I worked with RETEC, people were often surprised to find that we were a much smaller firm than they had imagined. They judged us in large part through the lens of our marketing activities—numerous journal and magazine articles, conference presentations, white papers, regulatory alerts, active participation in industry trade groups, and—at one time—the best environmental resource site on the internet. Our market focus also helped; as we concentrated our marketing efforts on just four core markets.

Certainly our accomplishments (e.g., being pioneers in bioremediation and risk-based solutions) constituted the substance of our reputation. But people learned about it through the various marketing vehicles we used to spread the message. And we spread the message mostly by sharing our notable expertise with our audience. We mastered the practice of content marketing long before I ever heard the term.

Serving buyers is the best way to close the Value Gap. Ask A/E service buyers what they value most between receiving great expertise (technical value) and a great experience (service value), and the answer will surprise most technical professionals. It's 50-50. That's the finding of a survey by Kennedy and Greenberg in their book Clientship. But when technical professionals were asked in another survey what distinguishes their firm from the competition, about 80% said it was their expertise.

The difference between those two perspectives is what I call the Value Gap, and it's substantial. In fact, I believe that closing that gap is probably the best differentiation strategy you can choose. That means, of course, providing exceptional client experiences after the sale. But it also means serving the client before sale by providing helpful advice and information—both in person and through your marketing.

We can all point to a few situations where this strategy backfired. You helped the client identify the best solution during the sales process and they hired someone else to implement it. But I can point to many more examples where giving some free advice made all the difference in winning the job—and helping build our reputation. I'll take those odds to do the right thing for the client, which is being helpful. What about you? I'd love to hear your perspectives on this topic.

The fundamental purpose of your business is to serve. You serve your clients and their constituents, and ultimately society at large. It's not pure altruism since you are well compensated for your service, but it's a high calling nonetheless. Every member of your firm should understand that he or she is in the business of serving others.

It's ironic, then, that you begin building relationships with prospective clients through a practice that's widely considered to be inherently selfish—selling. You may argue that self interest is not your intent, but your actions speak louder. When you spend most of the time in a sales call talking about yourself and your firm, that's rightfully perceived as self serving. Same when your marketing activities scream, "Look at us! Aren't we something." And when your proposals devote more space to touting your qualifications than telling the story of how you will help the client succeed, that hardly captures the spirit of service.

Do I sound a bit extreme? You would be correct to point out that my examples are common practice, something clients probably expect and therefore aren't likely to view as improper in any way. But my point isn't about impropriety; it's about ineffectiveness. Selling may be the norm, but most people hate being sold. If you're looking for an edge in the competition for new business, let me suggest you return to your core purpose...serving instead of selling.

People buy because they have needs, so helping them meet those needs would seem to be the most natural response. But sellers have needs too, and unfortunately those needs typically drive the sales process. The good news is that meeting client needs is the best way to meet your own. Serve clients well and you'll make more sales and keep more clients after the sale.

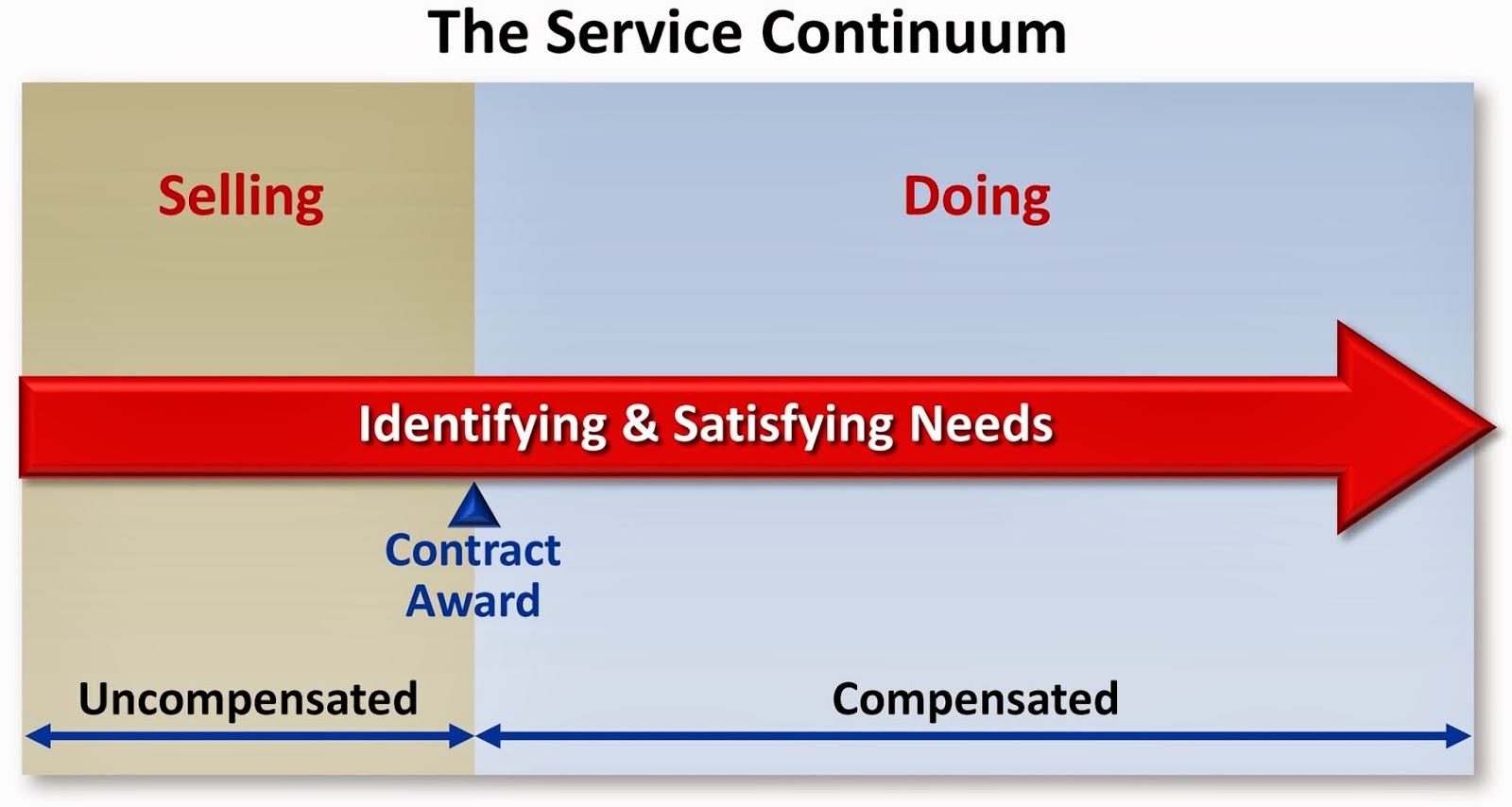

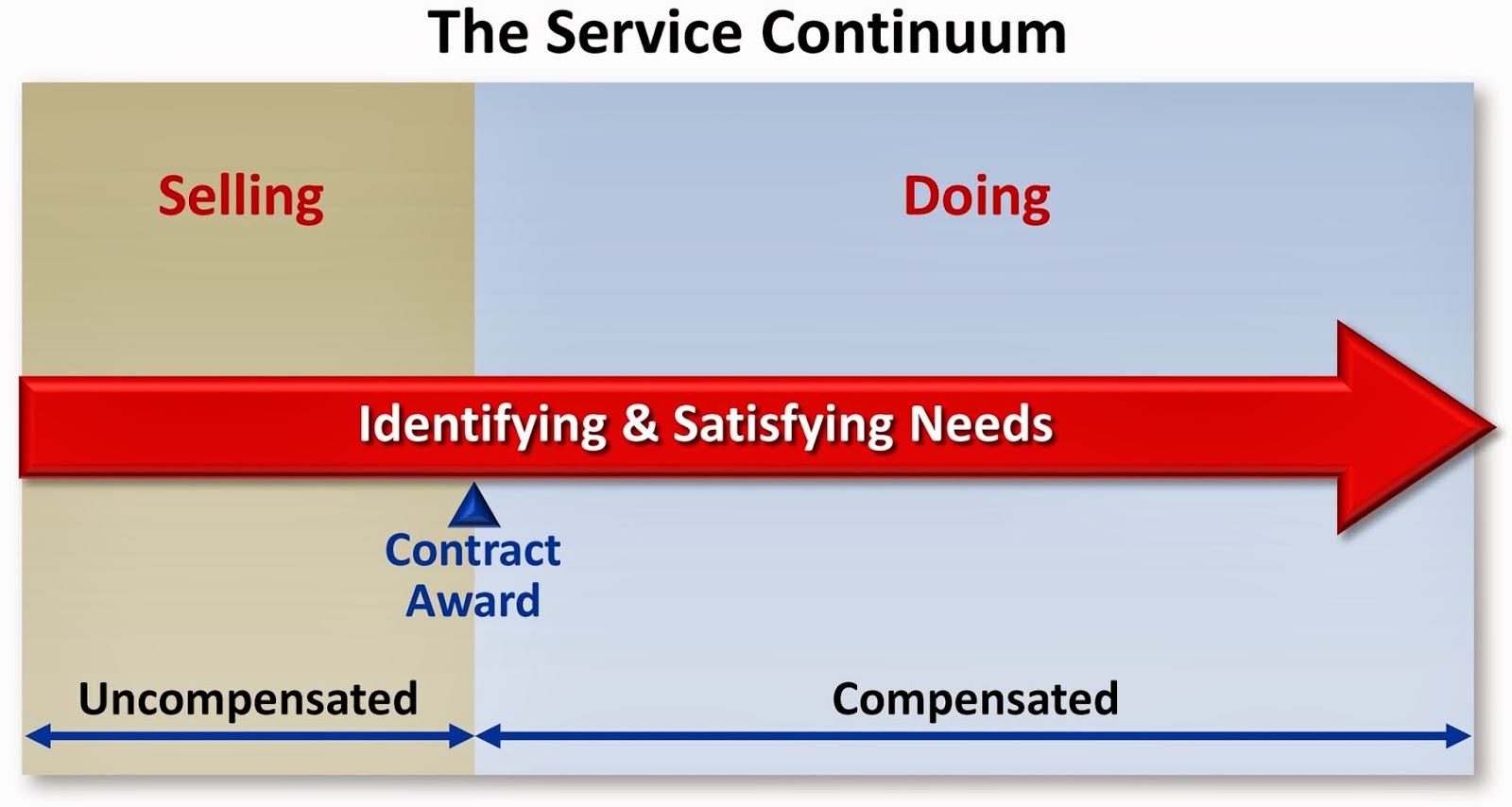

This basic philosophy is captured in the following diagram depicting what I call the Service Continuum. Rather than divide your interactions with clients into two phases—(1) selling before contract award and (2) doing afterwards—the Service Continuum suggests that there's only one fundamental activity. That's identifying and satisfying client needs, the essence of service. The primary difference between before and after contract is that you're getting compensated after the sale. So you have to scale your serving accordingly in the pre-contract stage.

The fundamental purpose of your business is to serve. You serve your clients and their constituents, and ultimately society at large. It's not pure altruism since you are well compensated for your service, but it's a high calling nonetheless. Every member of your firm should understand that he or she is in the business of serving others.

It's ironic, then, that you begin building relationships with prospective clients through a practice that's widely considered to be inherently selfish—selling. You may argue that self interest is not your intent, but your actions speak louder. When you spend most of the time in a sales call talking about yourself and your firm, that's rightfully perceived as self serving. Same when your marketing activities scream, "Look at us! Aren't we something." And when your proposals devote more space to touting your qualifications than telling the story of how you will help the client succeed, that hardly captures the spirit of service.

Do I sound a bit extreme? You would be correct to point out that my examples are common practice, something clients probably expect and therefore aren't likely to view as improper in any way. But my point isn't about impropriety; it's about ineffectiveness. Selling may be the norm, but most people hate being sold. If you're looking for an edge in the competition for new business, let me suggest you return to your core purpose...serving instead of selling.

People buy because they have needs, so helping them meet those needs would seem to be the most natural response. But sellers have needs too, and unfortunately those needs typically drive the sales process. The good news is that meeting client needs is the best way to meet your own. Serve clients well and you'll make more sales and keep more clients after the sale.

This basic philosophy is captured in the following diagram depicting what I call the Service Continuum. Rather than divide your interactions with clients into two phases—(1) selling before contract award and (2) doing afterwards—the Service Continuum suggests that there's only one fundamental activity. That's identifying and satisfying client needs, the essence of service. The primary difference between before and after contract is that you're getting compensated after the sale. So you have to scale your serving accordingly in the pre-contract stage.

What are we talking about in the uncompensated phase? Basic consultation: Helping clients characterize needs, identify potential solutions, and kick off projects (which you hope to do under contract). The key to making the Service Continuum really work for you is getting involved early when you can have the greatest influence over shaping the project. But serving prospective clients is a better approach at any stage in the process than traditional selling.

Let me respond to a common concern about this approach: "You're suggesting giving our consulting expertise away for nothing, which helps devalue our services." My experience has been quite the opposite. When you demonstrate your expertise rather than just talk about it, it's perceived value grows in the client's mind (assuming you're good at what you do). Your help likely prompts a sense of reciprocity, increasing the odds that the client will select you. If you've been truly helpful, it becomes less likely that the client will want to switch to someone else who's been less helpful (or not helpful at all).

The value of the Service Continuum has been well demonstrated, both in our industry and in others. So why is it not routinely employed? Because it's more work. It can be hard to get some clients to receive your offer to help. Doing a good job at it requires an investment of time. Many have no doubt have been burned by prospective clients who took advantage of their help but then hired someone else.

But the more your competitors resign themselves to traditional selling because of these perceived drawbacks, the better for you. That makes it easier to distinguish your firm from the rest by serving during the sales process. If the Service Continuum isn't your current approach, let me encourage you to give it a try. If you believe you are already serving sales prospects, consider how you might serve them even better. One thing I've learned is that serving ultimately serves you back.

So let me leave you with this reminder: Serve, don't sell. Show, don't tell. Try it, you'll do well.

First, have a really crummy proposal win rate to start with. Okay, so you knew there must be a catch. But I have, in fact, helped a few firms double their win rate or come close to it. They were doing poorly, so substantial improvement was easier to achieve. Whatever your current win rate, however, the strategies outlined below can help you improve upon it.

According surveys conducted by PSMJ and ZweigWhite, the median proposal win rate in our industry is about 40%. Yet I rarely encounter firms that are doing that well (maybe the better firms aren't looking for my help?). The number is inflated somewhat by including sole-source proposals, which represent a substantial proportion of proposals submitted for some firms.

For firms with win rates in the 20s—and I know there are many of you in this category—the goal of doubling your win rate is reasonable. The best performing A/E firms boast win rates of 50-60%. Of course, you don't want to look at your win rate in isolation. There's nothing gained by improving your win rate if sales are declining, for example. I'm assuming that bettering your win rate will be accompanied by overall improvement in your business development results.

With that understanding, here are some tips for doubling (or otherwise improving) your win rate:

Get out in front of RFPs. There's a disturbing number of firms out there that devote most of their BD efforts (in terms of total staff hours) to writing proposals. What that means, of course, is that for many, if not most, of those submittals there is minimal prior interaction with the client. That's a recipe for failure. I would estimate that the average A/E firm will win less than 5% of such proposals.

But for firms where this has become standard practice, changing is no easy matter. They tend to confuse higher proposal volume with being indicative of productive sales effort. The important issue, of course, is conversion rate. It matters little how much money you invest in the stock market if you get a poor return. Likewise, how many proposals you submit is not the right measure, but how many you win (see below).

To win more, you need to get out in front of RFPs, building relationships, gathering insight into client needs, and positioning your firm as the solution provider of choice. Do you have reluctant seller/doers? I recommend recasting the sales process, making it about serving prospective clients rather than selling to them. Organize your sales team so that there is peer support and accountability. Steer conversation in BD meetings away from proposals and to sales.

First, have a really crummy proposal win rate to start with. Okay, so you knew there must be a catch. But I have, in fact, helped a few firms double their win rate or come close to it. They were doing poorly, so substantial improvement was easier to achieve. Whatever your current win rate, however, the strategies outlined below can help you improve upon it.

According surveys conducted by PSMJ and ZweigWhite, the median proposal win rate in our industry is about 40%. Yet I rarely encounter firms that are doing that well (maybe the better firms aren't looking for my help?). The number is inflated somewhat by including sole-source proposals, which represent a substantial proportion of proposals submitted for some firms.

For firms with win rates in the 20s—and I know there are many of you in this category—the goal of doubling your win rate is reasonable. The best performing A/E firms boast win rates of 50-60%. Of course, you don't want to look at your win rate in isolation. There's nothing gained by improving your win rate if sales are declining, for example. I'm assuming that bettering your win rate will be accompanied by overall improvement in your business development results.

With that understanding, here are some tips for doubling (or otherwise improving) your win rate:

Get out in front of RFPs. There's a disturbing number of firms out there that devote most of their BD efforts (in terms of total staff hours) to writing proposals. What that means, of course, is that for many, if not most, of those submittals there is minimal prior interaction with the client. That's a recipe for failure. I would estimate that the average A/E firm will win less than 5% of such proposals.

But for firms where this has become standard practice, changing is no easy matter. They tend to confuse higher proposal volume with being indicative of productive sales effort. The important issue, of course, is conversion rate. It matters little how much money you invest in the stock market if you get a poor return. Likewise, how many proposals you submit is not the right measure, but how many you win (see below).

To win more, you need to get out in front of RFPs, building relationships, gathering insight into client needs, and positioning your firm as the solution provider of choice. Do you have reluctant seller/doers? I recommend recasting the sales process, making it about serving prospective clients rather than selling to them. Organize your sales team so that there is peer support and accountability. Steer conversation in BD meetings away from proposals and to sales.

Do fewer proposals, maybe a lot fewer. My client was an engineering firm that wasn't growing and hadn't been profitable for the last few years. They needed a quick turnaround on the BD front. Among my recommendations: "Do half as many proposals in the coming year." You could almost hear their jaws hit the table. But they were averaging over 11 proposals per month (with a one-person marketing staff) and winning only 26% of them.

They grudgingly accepted my challenge and we managed a 40% reduction in submittals (one office refused to go along), while raising our win rate to 46% and increasing sales by over 30%. How? By spending their time more productively. We made it harder to get corporate support for proposals; each had to pass a tough go/no go decision process. Thus we spent more time on winning efforts and a lot less on losers. We also substantially shifted the effort to pre-RFP from post-RFP, as suggested above.

Make your proposals different from the rest. That is the objective, isn't it? Yet in reviewing hundreds of proposals over the years, I've seen a remarkable sameness about them. It's as if fitting in was more more important than standing out. I compiled a 75% win rate during my time as corporate proposal manager by creating proposals unlike the competition's.

There are two areas where such distinction is readily available:

- Making your proposals prominently client centered. Most proposals feature the seller, not the buyer. RFPs help promote this by requesting more information on qualifications than about the project. But you don't usually win on qualifications, rather on having a better understanding of what the really client wants and a better solution for getting there. Hint: You can't make your proposal client centered if you haven't been talking to the client before the RFP is released.

- Making your proposals user-friendly and skimmable. Proposals are decidedly better looking than they were when I started writing them in the mid-1980s. But I don't think most of them are any more functional. A strong proposal is easy to read and navigate. It says the most in the least amount of words. If you doubt this is a significant advantage, you've probably not had clients praising you for how refreshing it was to read your proposal.

Stand out in the shortlist interview. I've long found it ironic that firms will invest far more time in a proposal with long odds than a shortlist interview with much better odds. The first step to substantially improving your win rate at the shortlist interview stage is to work harder at it. But don't stop at working harder; you've got to work smarter as well.

Client feedback indicates that comfort and fit are key factors at this stage (and, no, you won't find those among their formal selection criteria). Yet clients routinely put your team in a setting where they're typically less comfortable—making a formal presentation. One way to overcome this is to ask a few questions during your presentation (ask permission to do this first). This invites dialogue, a context in which most technical professionals come across as much more confident and competent than in presenting.

If you can spend most of the time talking with the client selection committee rather than talking at them, you've put your team at an advantage (if you're well prepared). Even the most polished presentation—which is often more acting than interacting—cannot compete with a great conversation. Again, you're not ignoring the instruction to make a presentation, but you're making it more interactive, which is better for both parties.

Winning the shortlist interview also depends on your advancing the narrative of your proposal. Expect to add some new insights and details to what you submitted earlier. Perhaps it's a concept design or a cost estimate. And don't ignore talking about the working relationship (everyone else will). Clients are wondering at this point what it will be like to work with your firm, so talk about it. Hopefully, you already demonstrated this in part through your service-driven sales process.

Content is king in marketing professional services. Yet most A/E firms are content poor. They don't produce enough articles, papers, presentations, webinars, and the like to sustain an effective content marketing effort.

Content is king in marketing professional services. Yet most A/E firms are content poor. They don't produce enough articles, papers, presentations, webinars, and the like to sustain an effective content marketing effort.